Accurate representation of diverse skin tones in photography has been a longstanding challenge due to biases toward lighter skin in traditional reference materials used for film and digital photography, such as Kodak’s “Shirley” cards and the Fitzpatrick scale. These and other tools, such as the ColorChecker Classic, have offered limited ranges of skin tones and do not capture the full diversity of human skin, including variations in shades, undertones, and exposure behavior.

It started with two mannequin heads...

And some webcams.

The "Richard" mannequin is shown on the left, and the "Alexis" mannequin is on the right. Both scenes are captured under the same lighting conditions with a basic $50 webcam. The overall scene brightness appears the same, but we see that the Richard mannequin is underexposed. This is a problem.

The two mannequins were also captured using a $300 webcam, as shown below. Again, both scenes are captured under the exact same lighting conditions, but the scene brightness appears very different due to an auto exposure (AE) algorithm that uses face detection. The algorithm priorities exposure of the face, but at the cost of overexposing the rest of the scene. This is also a problem.

I repeated the process for a third, mid-price webcam that also uses a face-based AE algorithm, and got similar results—a well-exposed face, but over-exposed background and charts. I additionally captured a control scene, with no detectable face, with each camera.

I then calculated the average Delta E 2000 (a color accuracy metric) for all of the ColorChecker patches in each image.

Unsurprisingly, the error is high for the Richard mannequin scenes where face-based auto exposure is applied, because the ColorChecker in these scenes in visibly overexposed.

Perhaps more surprising is the error in the control scene for the $300 webcam. It is higher than the error for the Alexis scene. Meaning that having a lighter face in the scene actually improved the overall color and exposure accuracy. That is a big problem.

This sent me down a rabbit hole on the history of photography and the perpetuation of racial bias from film photography into modern digital photography. I've heard plenty of arguments about how this issue is simply due to the physics of light. This is simply not true.

Darker skin is not harder to photograph because of physics. It is harder to photograph when the imaging system is not designed, trained, or calibrated with darker skin in mind.

While darker skin reflects less visible light, modern sensors easily accommodate this range of reflectance. The real challenges arise from biases embedded in exposure algorithms, color processing, training data, and calibration targets. For decades, film stocks, reference cards, and color appearance models were developed using limited skin-tone examples, leading to imaging pipelines that implicitly treat lighter skin as the default. These legacy assumptions persist in today’s auto-exposure, white balance, face detection, tone-mapping, and color-calibration algorithms, all of which influence how skin is rendered. As a result, darker skin tones may be underexposed, desaturated, or inaccurately shifted. Not due to inherent difficulty, but due to insufficiently representative calibration and training data.

So, considering that I work for a company that designs test targets for camera testing and image quality analysis, I could tackle one of the causes of this perpetuated bias: the lack of standardized test charts with a range of skin tones.

The ColorChecker was introduced in 1976 and contains only two skin tones that are hardly representative of the wide variety of tones. Yet, it is still the most commonly used chart for color correction. Other charts, such as the ColorChecker Digital SG, have since added additional skin tones, but this only solves part of the problem in modern digital photography. As we saw in the case of the face-based AE algorithm, uniform patches can only tell so much of the story. If detectable faces are what drive these algorithms, then detectable faces need to be used during the testing and tuning process. Few standard face charts exist, and none are as simple to use as a standard ColorChecker chart.

So that led to the creation of a set of photographic test targets featuring faces of a wide range of skin tones.

The first iteration of the charts followed the Monk Skin Tone scale, created by Harvard Sociology Professor Ellis Monk in an effort to represent a broader range of geographic communities.

The issue here is that the Monk Skin Tone scale is intended to be used as an annotation tool for machine learning algorithms. The tones correspond well with rendered skin tones in images and how humans visually perceive and group them, but they are not representative of actual physical skin colors. This meant that when the charts were photographed, the results did not reflect the process of photographing a real human.

So I took a step back and adjusted the faces to more closely match colors of real human skin. There are, of course, spectral components of real skin that cannot be fully mimicked with print, so metamerism is a concern when using these charts under various illuminants. But overall, the initial results were promising.

But we could do better...

Were these charts actually representative of real skin?

To understand that, we needed data from real humans.

So I took to the internet to find some people willing to let us photograph them in our lab under a ton of lighting conditions and exposure settings.

And measure their skin with a spectrophotometer.

And participate in a psychophysical study to choose preferred exposure levels.

It was so cool.

Months later, I'm still sifting through data.

With these images, the goal became: Can I print a photograph of this person that, when photographed under the same conditions, looks like the original image?

If we could do that, or get really close to that, then we would have printed skin tones that correlated with real skin that coud be used for camera testing.

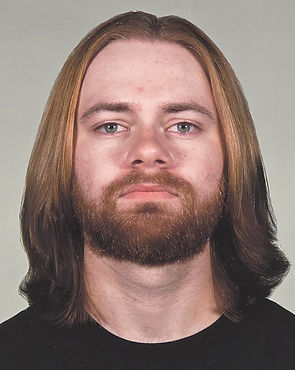

For example, this was one of our participants.

Except that one is a chart.

<- This is from the original picture.

Not perfect, but we're getting closer and closer as we make adjustments. We are doing this process for all 10 of the skin tones, and will stress test them under the same series of lighting conditions, verifying them against the original images.